September 21, 2010

Here is an interview with Alberto Garcia (also known as El Tio Berni). He is the webmaster for the excellent site www.entrecomics.com and is, without a doubt, a deep thinker with a good sense of humor. I am posting this here because of his wonderful questions, and the fact that entrecomics.com will post the interview (in October) in Spanish.

AG: You come from animation and, as far as I know, after a few minicomics, you did PERCY GLOOM, a graphic novel more than 150 pages long. First of all, what attracted you to the comic medium to tell your stories? Did you find your previous experience in animation helpful?

CM: Comics is still a very open medium. As a writer/artist you set the limitations of skill and honesty.

AG: You presented Fantagraphics 1/3 of PERCY GLOOM already completed when you were looking for a publisher and they liked it. Weren’t you scared at the possibility of drawing so many pages without knowing if it was actually going to be published? -

CM: In animation we draw many, many drawings and throw away even more! This way of working prepared me well for comics. I was having so much fun creating Percy Gloom that I would have finished it even if Fantagraphics had rejected it.

AG: You said that when you were a child you read MAD and PEANUTS (actually, Percy resembles vaguely a grown up Charlie Brown -and his stomach hurts, too) and later you were introduced to the work of the biggest graphic novelits of our times, i. e. Ware, Seth, Clowes, Spiegelman... How much current work (satire, comic stips, graphic novels) influences and shapes your work?

CM: The simple fact that these artists have been true to themselves has inspired me to go forward with my own ideas.

AG: Could you tell us about your non-comic influences (film, literature, painting, etc.)? Where in your work can they be seen?

CM: Oh, this is a difficult question, because in modern life there are so many influences. In painting I love the old Flemish school and the German Expressionists, as well as Japanese woodcuts. In architecture I most admire the Romanesque period. In terms of film, music, literature, there are too many influences to name! It would take me months to think of them all.

AG: Reading interviews with you and reviews of your work, I’ve found references to people outside the comic field, like George Orwell, Franz Kafka, Walt Disney, David Lynch, William Shakespeare, Lewis Carroll, while you were not compared directly to any other cartoonist. Why do you think this is so?

CM: This might be because my interests have been varied. I really don’t know much about comics and don’t read them very often. Most of my reading is in non-fiction, usually because I’m researching for a new book.

AG: Rereading your books for this interview I started taking notes, but at some point I had to stop. Some of the many ideas (often abstract ideas) that you introduce in your work are not easy to jot down in a line or two, they are too complex, admitting several interpretations with many ramifications. Did you do this purposefully? I mean, not being too direct, not trying to convey your thoughts in a more concrete way to the reader.

CM: A book is a conversation between reader and author. Conversations usually don’t end neatly, with unshakable conclusions. Everyone has a different view of events. I find it’s very exciting to offer people a place to keep finding new interpretations. The stories have an internal logic—everything is deliberate--so even if people are uneasy with the ideas they will at least find a consistent experience.

AG: Your work is plenty of symbols. Do you think that symbolism is the best way to convey abstract ideas?

CM: This depends on the kind of information you are trying to convey or elicit. We live by symbols, even if we think of ourselves as rational, verbal beings. Symbols can serve to bypass a lot of our conscious resistance to deeper ideas.

AG: Something quite curious about your work is the way you depict your main characters. Almost all of them have a grotesque look, and I don’t know if it is, somehow, a way to portray their inner self, or if it is just that you like to draw them this way. This peculiar look also makes them less generic and easier to stay in the memory.

CM: Have you noticed how little expression is possible with pretty characters? Beauty is so dependent on exact proportion that if you show any distortion the character ceases to be pretty. For this reason I find pretty characters very boring to draw! I want to get at all the raw emotion, and to do this I have to distort. Or to think of it another way: a classically beautiful character’s features are perfectly balanced. When you look at a beautiful person you relax. With a grotesque design you have all these contrasts; they heighten your perception of each feature--you can never quite relax because you are always searching for what those distortions point to. Finally, a grotesque character points us to our inner selves, as you said. If we can find him/her beautiful then we have accomplished something good.

AG: PERCY GLOOM and at a lesser extent TEMPERANCE too, have a pathetic feeling but at the same time there’s some humor. I wonder if it is just a device you use to tone down the incredible level of sadness of some situations or if it is “organically” part of the story you want to tell.

CM: Have you ever cried so hard that you started laughing? Or laughed so hard that you started crying? They are on the same continuum, absurdity in the midst of pain or vice versa. However TEMPERANCE deals with such dark sides of human behavior that I found it hard to incorporate too much humor.

AG: Reading your two graphic novels I had the feeling that your characters start with a defined personallity that changes as the story develops. It’s like instead of going forward, they somehow grow up. By the end of the stories, they have changed through some incomplete catharsis, but it’s not really clear if the situation has really changed or if things remain the same or start a new cycle. Do you think that the subjects or problems that you address don’t have a solution or that you don’t know what it would be? Or, perhaps, do you not want to be too explicit?

CM: It’s the last thing you said. I want to leave things open for the readers so that they can find themselves in the characters. And regarding catharsis: in my opinion it doesn’t have to involve overt drama or violence. For instance, on p. 150 of PERCY GLOOM he looks directly at the reader, saying nothing. He has released his fear and confirmed his commitment to participate in life. This is his catharsis, and it is also the quietest moment in the story.

AG: In PERCY GLOOM we can find a commentary on overprotection, both from ourselves and from “above”. Do you feel that, as a society, we are overprotected? How does it affect our lives?

CM: Yes, definitely, but there is some benefit to this, too. Nurturing fear can really help the economy! Just think of all the products and services available that are based on people’s fears. I am not sure if the world is any less safe now than it was years ago. If anything, in real terms, it is probably safer. Crime is down in many areas. Medical care has improved for many of us. But we have gotten into the mindset of overwhelming ourselves with fears and warnings at every level of existence. We have created many more stressors, and these can be harmful to us and to the children we influence. Mental illness in this era is a growing issue. It can be triggered by stress at key points in life. The issue is, how much of this stress have we created? Can we alleviate it? We can, of course, but we have to slow down and be aware of the world we are making.

AG: Characters in PERCY GLOOM look for security by performing rituals: chanting mantras, eating specific foods, cooking people alive... while on the other hand, removing a simple cobblestone can topple everything. Are you implying that security in our lives is delusional?

CM: Yes! You can’t escape change, and you can’t escape the weaknesses of your own species! Just look at our current economic crisis. Those of us who were very careful with our money still lost it, because somewhere in the system there was greed and deception. Human flaws are never contained. They affect everyone. We are always afraid of the wrong things, the little things, things we can understand and control, while these big forces are changing everything! All you can really do is to not be too attached to things, which is very challenging!

AG: Trying to avoid pain and death, some of your characters sacrifice themselves (like the self-mutilating Leo) or the ones they love (Tammy and her parents), but in the end I think the idea is that security is not worth the sacrifice. Isn’t it?

CM: The best security is to have people you love in your life and to tell them how much you appreciate them, don’t you think? All you have in your life are the connections you make. In the end, when Tammy’s town collapses, people are reunited. Not all change is bad. Not all revelations are harmful. Minerva goes through a similar situation in TEMPERANCE, though the collapse is more under her direction.

AG: Also, there are at least a couple of sequences where knowledge is seen as dangerous by that people obsessed with security (Leo says, “Books can kill!”, and big ears are seen as a deadly sign). Can knowledge save us?

CM: That depends on the kind of knowledge. I suppose the right kind of knowledge can save us from fighting nature, from fighting death and suffering. Human beings—all beings—are naturally inclined to learn new things. Depression is often caused by a lack of stimulation, the feeling that there is nothing new to learn. So the act of acquiring constructive knowledge can save us from depression and hopelessness. We can enjoy the exhilaration of learning on a regular basis: having a picnic in the park, watching the birds, reading a book, doing a math problem, staring at a painting, having a lively conversation like this one. Remembering your dreams provides another kind of knowledge. Simply being quiet might be the best kind of knowledge.

AG: Tammy is afraid of death, so she decides to erase it from her life, getting rid of those who are about to die. On the other hand Percy’s dead girlfried thought just the opposite, that life was nothing but a farce, and sought to run away from it through death. Percy seems to be halfway, he’s scared of life and he’s scared of death. Do you think that this is how the most of us feel?

CM: I suppose we feel these things in varying proportions throughout our lives, depending on our age and what kind of losses we have experienced. Both of the cults in the story are expressing deep human emotions and the desperate strategies for dealing with the inevitable!

AG: If you don’t mind, let’s discuss TEMPERANCE a little bit. First of all, I noticed a small chage in your drawing style. I found it much more expressive, with a clear improvement in the way the characters move in the panels and through the page. Sometimes the drawings look sketchier than those in PERCY GLOOM, but, curiously, they feel more real to me. Did you purposefully change some of your drawing devices, or was it just a natural evolution of your craft?

CM: This was such a different story, so it needed a different style, and different character designs to express more intense emotions.

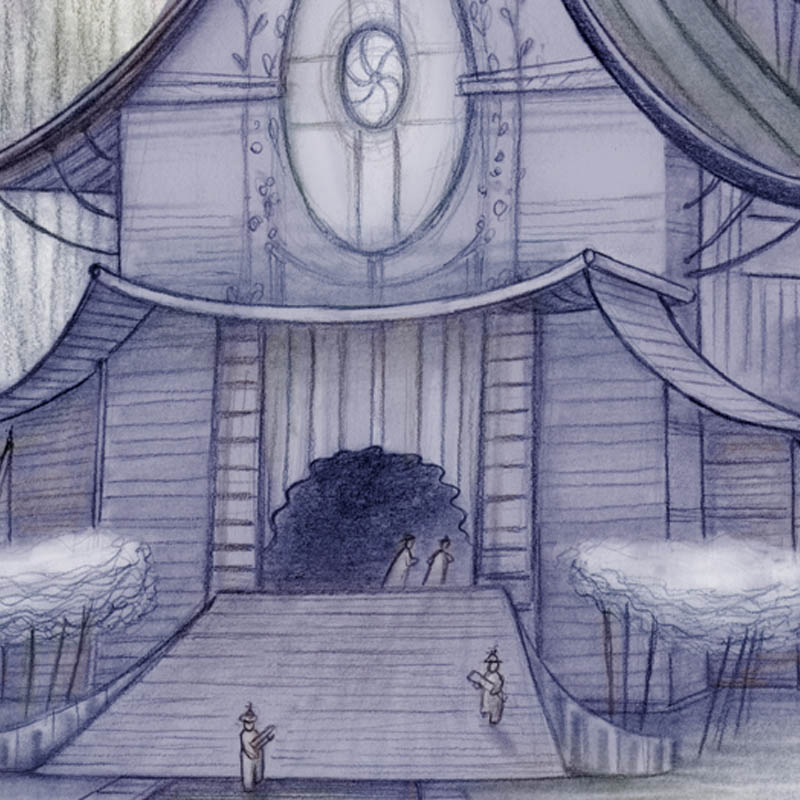

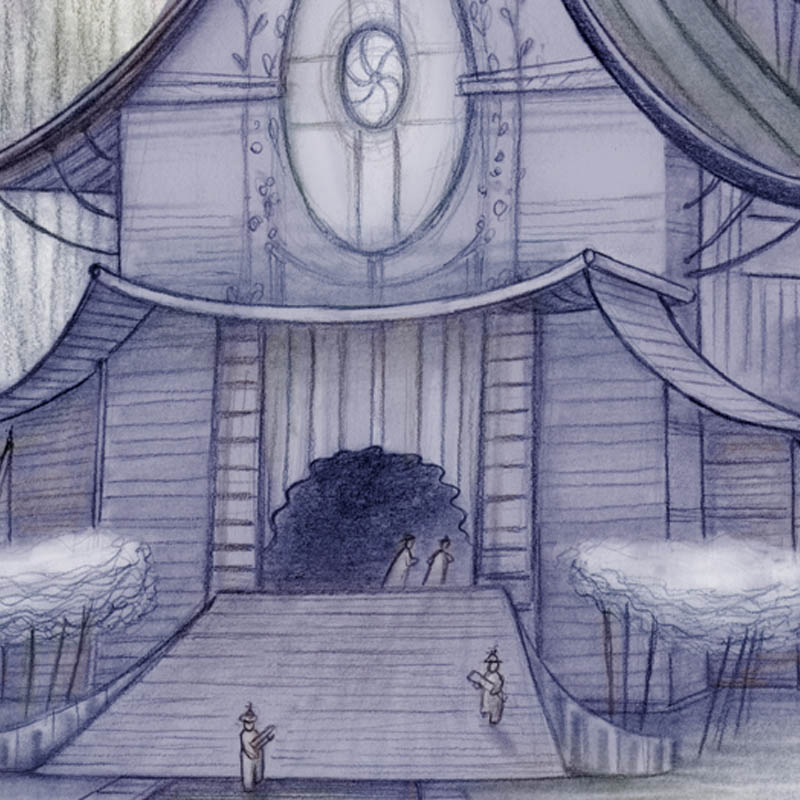

AG: Another interesting device used in both of your graphic novels is the passing of time into a single panel, with the characters appearing in different positions as they walk and speak their dialogue. It’s not an uncommon device in comics, but neither is it used too often. How did you arrive at it? Is it somehow connected to your work as an animator?

CM: This has two antecedents. The first is mediaeval art, when different life events of a saint were all depicted in a single painting. The second is called the “layout” stage in animation. Layout is an intermediate stage between storyboarding and final animation. It is actually a map or plan of a character’s position in space at specific points in time (or frames of film).

AG: In TEMPERANCE it looks like you are more comfortable with narrative, that you use panel size and composition more consciously to create rhythm and to convey ideas. Is it true?

CM: I am sorry to disagree with you! I simply took a different approach for a different kind of story. The plotting just seems more deliberate and evident in TEMPERANCE. PERCY GLOOM had the feeling of absurdity and randomness, but it was very tightly plotted, too. It’s just that people have different expectations of what a plot should be. Having a narrator probably made TEMPERANCE seem more traditionally constructed. In the case of PERCY GLOOM there was no narrator, and we had to share the main character’s confusion at every stage.

AG: I have to say that, even though I very much liked PERCY GLOOM, I liked TEMPERANCE even more, not only because I think you improved your narrative skills, but also because to me, some subjects are less obviously treated (not that PERCY GLOOM was so obvious, anyway). I mean, TEMPERANCE is a more complex work as a whole.

CM: Yes it is, and it is more demanding on the reader, too. I’m really glad you had the patience for it! With PERCY GLOOM I felt more of an urgency to say things directly, because we were still a very frightened world after 9/11. Sometimes people just need to be comforted.

AG: Some of the main subjects in TEMPERANCE are similar to those in PERCY GLOOM: fear, dependance, and oblivion, to some extent. But on the other hand, in TEMPERANCE you introduce new subjects: war, destruction, violence. Which ones do you think are the main similarities and differences between both of your works?

CM: Both stories deal with lies versus the truth. Sometimes the lies are more compelling, comforting, unifying and entertaining than the truth, so they persist. When they persist they become memory, and, with time, it is very hard to separate the two. Each of us is a story, an ongoing event of memories and interpretations. What we don’t remember says as much about us as what we do remember.

AG: Each one of your characters in TEMPERANCE symbolizes some kind of force of nature or idea. Did you find difficult to make this fit into a believable character?

CM: I spent a lot of time building these characters in the way an actor would, examining their early lives, their needs, and their methods for getting what they wanted. Even when you are dealing with a personified force you have to begin with emotions, the primal language of humans. We humans may have objective tools of measurement, but we still see and interpret the world in human terms, through our own unique set of perceptions.

AG: Minerva is quite a complex character: in her we can see two opposing forces trying to break free. One of this forces is love, the other one... well, could you explain it a little bit? Could you talk also about the rest of the cast?

CM: In this story everything, every emotion, flows out of the interplay between destruction and creation and human beings’ responses to these. Some people, like Minerva, live much closer to these forces than the rest of us, and they learn to manage the forces on the broader social level. Early in the story Minerva learns a hard lesson: to favor one force over another is a terrible mistake. She had lived under the false belief that destruction was where all power resided. She spends the rest of her life looking for ways to bring creation back into her life. When Minerva, Lester and Temperance find and accept the balance of forces, their world opens up. They can truly start to live.

AG: It seems to me that in TEMPERANCE, some of your characters don’t have free will. Pa has to do what he has to do. Minerva has to think about all the other people, so she can’t care of herself. Lester cannot be free because his memories are not his own. But all of them struggle like hell to be free.

CM: We have to acknowledge here that free will is a concept of the ego. We are part of an interdependent system. We make decisions based on our context, and our decisions change the context. Even if Minerva guides people with storytelling, they are willing to be guided. They are showing her what they need, by the stories they respond to. The children of course will ask questions, and some of them will keep asking questions, because they did not volunteer for this deception; they were born into it. Even though they have been weaned on the language of lies, their internal logic senses that things don’t exactly make sense. Still, they are part of a community and there is strength and security there. On the more elemental level of forces (destruction and creation, Pa and Peggy) there is a simpler, more obvious interdependence. Pa cannot exist without Peggy, just as oblivion cannot exist without memory. They are the guardians of chaos, forming and re-forming matter and energy at all levels. (Pa actually describes this process when the doll is leading him through a narrow passage, pp. 174-175).

AG: It’s easy to find connections between TEMPERANCE and some dynamics in the US, especially if we take into account the foreign politics, war in the Middle East and the fear in US citizens that might make them easy to manipulate. But I think that reducing your book to this wouldn’t be fair, because it has a broader meaning. Could you elaborate on this?

CM: Thank you for saying this! It would be very boring for me to work on a book based simply on current events. Current events are just another ripple in history. In this story I am more interested in the forces underneath the activity. Everything seems to be a struggle over mortality. It is not simply that we don’t want to die; we don’t want to be forgotten! What is the worst thing that the destructive force can do? It can erase all memory of your particular existence. Think of the villages washed away in floods: entire families, their possessions and stories, simply gone! This is when you have to wonder at your own uniqueness. If you are convinced that you stand apart from the systems of nature, then any sort of destruction is horrifying. Our sense of uniqueness is at the heart of human suffering. It is so deep in our complex, individualistic nature that we have to work very hard to transcend it, if we ever do. This is why the character of the doll is so important. It has undergone many physical changes, but it keeps a constant awareness. The nature of the wood keeps it resonant to the wider world.

AG: Another thing that I’d like to point out is your use of fantasy. When we think of fantasy in comics, unicorns, gnomes and castles, even swords and dragons come immediately to our minds. Fantasy in your work is something completely different: you use fantasy settings to set the mood, but then you try to talk about things that we usually see in other types of comics, often autobiographical or stories more grounded in reality. What does the fantasy genre add to your stories? Do you think that perhaps it’s easiest for the reader to accept symbols and parables in this kind of comic?

CM: The fantasy genre allows me to bring together a wide range of symbols to illustrate ideas. Realism is a fine genre, but for me its limitations do not allow for a full range of ideas to be explored. Realism does not respect dream symbols, for example, and dreams are such a large part of our lives.

AG: Are you satisfied with your two books? Do you really like them?

CM: Yes, not simply for the books themselves, but for what the process of making them has taught me. My hope is that people are being helped by these stories in some way.

AG: Could you tell us about your future plans?

CM: Right now I am simply exploring other ideas. I really don’t know what’s next!